Principal-Agent Problem and its Impact on Finance and Crypto

Principal-agent problem; 2x2 matrix; Management theory; Banking; DAOs

In almost every human workplace, there is a principal—the business entity who is hiring another for a task—and an agent—a person (entity) hired by the principal for his or her product or service. This can be represented in pyramidal organizational charts, which depict the hierarchical relationship of a company: Venture Capitalist to CEO, CEO to Manager, Manager to Engineer, etc.. In an org. chart, all of the edges (in the diagram below, every side of the rectangle or triangle) have a 2 x 2 matrix, which will be discussed later.

As Investopedia defines it, the principal-agent relationship is

…an arrangement in which one entity legally appoints another to act on its behalf. In a principal-agent relationship, the agent acts on behalf of the principal and should not have a conflict of interest in carrying out the act.

Some examples of this relationship are a venture capitalist and a CEO of a company, a homeowner hiring a plumber, or an investor giving capital to a fund manager.

The “problem” arrives when an agent neglects this relationship and pursues his own agenda or personal interests. This problem stems from human nature wherein no two humans fully coincide with one another, leading to a trolley problem scenario: If you push one hard enough, there is often a divergence in one’s incentives. The principal-agent problem is present in the real world every day, so much so that people often don’t realize it’s occurring. An instance of this would be a plumber being compensated for servicing a house when he did not fix the running toilet (in other words, being paid for doing a lazy and/or poor job).

2 x 2 Matrix

Almost all people want to avoid detrimental scenarios involving loss, especially the lose-win scenario (orange box) if you were looking from a principal’s perspective. There are a couple of ways to limit the principal-agent problem:

A simplified strategy would be for people to read their contracts and to design contracts such that both parties benefit. However, this is easier said than done with human nature and greed tempting one to diverge from the green box below.

Have the compensation of the agent be tied to his performance so that conflicts of interest are limited, or even eliminated.

The second “solution” is evident in many startups who successfully avoid the lose-win (conflict of interest) scenario by having no capital to distribute to employees until an exit. This hinders the hypothetical possibility of a zero-sum dynamic in a startup where 51% of the company votes out the other 49% of their deserved money.

The best way to offset conflicts of interest in the 2 x 2 matrix is to diagonalize it as much as possible with a line going through the red and green boxes such that the principal and agent win together and lose together. This eliminates the temptation for one of the groups to defect to a win-lose scenario.

When in a relationship with three people, it becomes a 2 x 2 x 2 matrix with eight total outcomes. This (win-lose) x (win-lose) x (win-lose) becomes a Cartesian product. As the matrix becomes more and more populated (like in a very complex org. chart), it becomes a 2 x 2 x 2 ^ n with n representing the variable for people.

Moral Hazard and Adverse Selection

The issues of moral hazard and adverse selection can lead to the suboptimal win-lose situations in the principal-agent problem:

A moral hazard occurs when an agent gets involved in risky behavior or does not act in good faith because the agent knows he does not bear the responsibility for the consequences of these acts. Moral hazards tend to pop up in the principal-agent relationship when the principal hires an agent to complete tasks that benefit the principal solely. This is evident when a salesperson is compensated at an hourly rate but receives no commission for any of his own sales. This could ultimately lead a salesperson to allocate less effort into his work since the rate of pay is not affected by his performance (how successful the salesperson is). While the agent is still getting paid for doing less work, the principal loses by not getting the performance he expected when hiring the entity. This results in a lose-win scenario on the 2 x 2 matrix (orange box) above.

Adverse selection transpires when either a principal or agent makes poor choices based on asymmetric information—information that is only available/in the possession of one of the parties. This leads to many win-lose scenarios such as a lazy agent being hired without the principal knowing that the agent is lazy. In the financial world, sellers are able to take advantage of buyers through asymmetric information with the seller possessing more information on the good being sold than the buyer.

Interesting “Solution” to Moral Hazard in Australian Banking System

In Australia, digital currencies have been proposed as a solution to eliminating moral hazards in the banking system. In the current system, bank officers make high-risk loans because they reap all the benefits of doing so while also bearing none of the losses if/when the loans go bad. This proposal to the Australian government aims to leave the banks with the liability for defaults, theft, and fraud after removing the loans and deposits from the balance sheet of banks. This paper then proposes to create a digital currency that serves as a legal tender, meaning that coins, banknotes, and digital currencies would be accepted as the same for repaying debts. This would eliminate moral hazard in the banking system as deposits would no longer be at risk, removing the incentive for bank officers to make high-risk loans. The risk in the Australian banking system would then be placed on the people earning income from making the loans in the first place.

Solution to Principal-Agent with Crypto and DAOs

Unlike investing into traditional investment funds where the power lies with a central authority (a fund manager), the decision making power in DAOs lies within a group. DAOs are therefore structured for the benefit of a pool of investors rather than for an “agent” like a fund manager.

As DAOs represent the large variety in governance structures within an organization through pooling investors with equal say, they can both solve the principal-agent problem and further complicate it. The structure of a DAO is:

One governing law which is the smart contract regulates the behaviour of all network participants.

Once the protocol is deployed, it is independent of its creator and can be governed only by a predefined majority of network participants.

Tokens act as an incentive for network validators.

Once a crypto program is deployed, it is independent, meaning that it runs autonomously with no mind of its own, expending through the program that its creator gave it. Since a crypto program, like a DAO, runs autonomously packet-to-packet rather than through a banker, it “solves” the principal-agent dilemma.

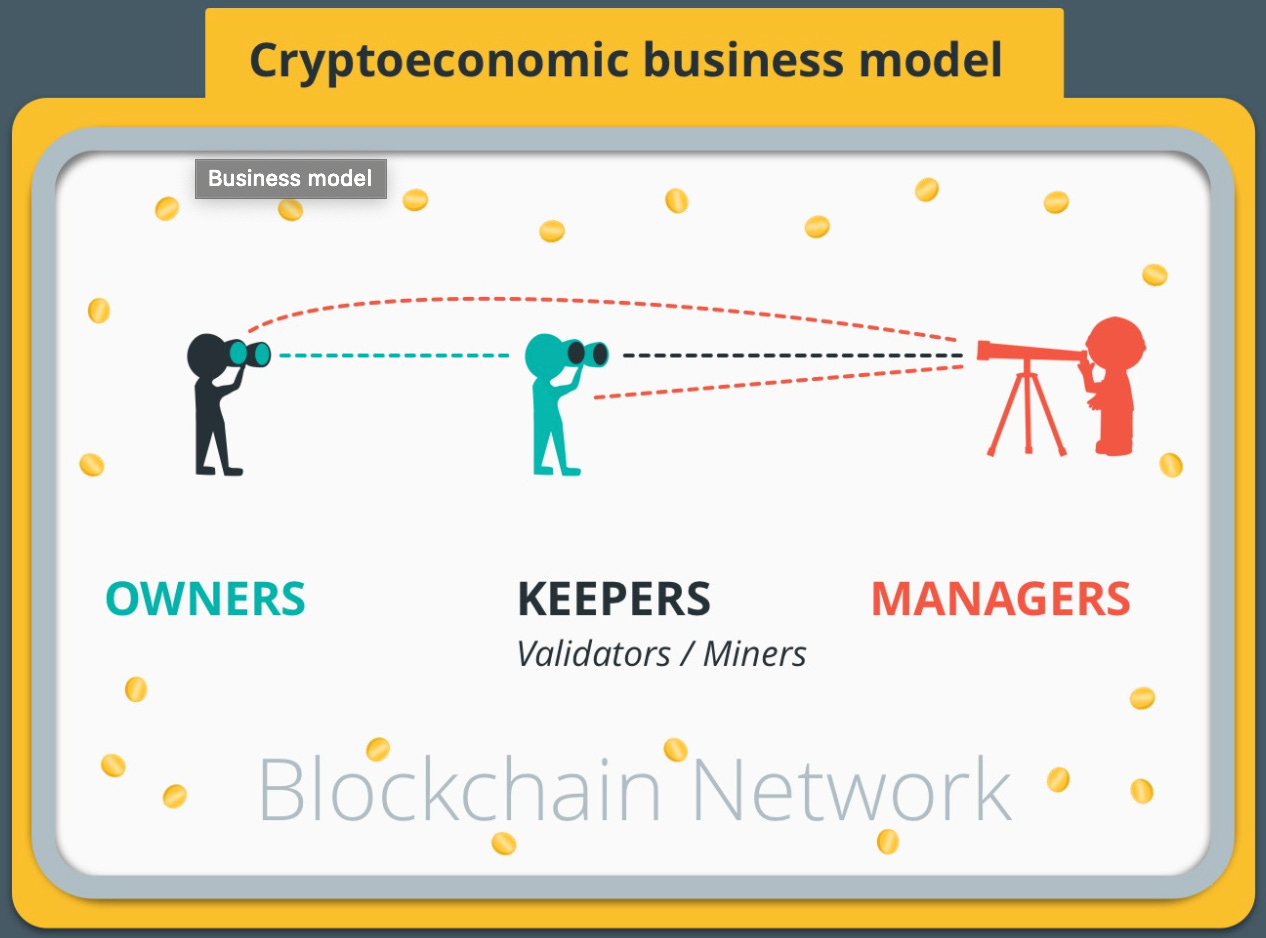

However, this is not always the case for cryptocurrencies (DAOs are considered crypto co-ops as they are built with blockchain technology). When the Keepers of a Blockchain network—those who work on a network as miners and validators in exchange for tokens—are involved, the Cryptoeconomic business model has a 2 x 2 x 2 matrix with managers, owners, and Keepers. Now, owners and keepers have interests that depend on the efforts of a manager—and can also diverge from one another.

In theory, managers in the crypto model should have “skin in the game”, which would motivate them to grow the token’s CUV/DEUV (keep in mind that CUV and DEUV might not be the proper way to calculate the value of a cryptocurrency, it’s just one of the more prominent calculations) with the hopes of selling the tokens for a profit at some later date. This layout would keep the interests of managers, Keepers, and owners aligned. However, many don’t see the current utility value and discounted expected utility value to retain all of its value in crypto. This could then drive the manager’s motivation to create long-term value for the blockchain network dilution.

Although the democratic voting system of a DAO could be beneficial to eliminating the principal-agent problem by limiting conflict of interests, its voting system has some loopholes. Here are some of the drawbacks of a DAO:

51% attack: If one person acquires 51% of the total supply, the power of the DAO can be completely taken by that person.

Rules that govern a DAO could be complex. Participants of the DAO may lack the technical expertise to understand the code and make meaningful contributions.

Any code changes in reaction to bugs or hackers could get delayed due to the approval process. Important security updates are dependent on the majority votes.

Not fully decentralised as the name suggests. Despite being geographically decentralised, the DAO is still centralised by the smart contract that governs the network.

Uncertain regulatory restrictions that could be enforced.

Conclusion

While it is not yet clear as to whether cryptocurrencies fall into the principal-agent dilemma or resolve it, it is apparent that certain aspects of the crypto model prevent conflicts of interest from occurring. At the same time, however, other aspects contribute to a greater conflict of interest.

As trust in society decreases, it is becoming more difficult to maintain a scaled organization of human beings (refer back to the traditional org. charts) due to increasing levels of divergence in this individualistic era. As society shifts towards a generation favoring absolute freedom where everyone is their own boss, zero hierarchy in an organization could be possible.

Additionally, with management becoming increasingly automated, its popularity has grown as well since programs and robots do not experience divergence. It will be interesting to see if more people turn to automated management organizations or if they continue to maintain the current management practices of a principal hiring an agent for paid labor.

Further reading

Crypto’s Moral Hazard - Bloomberg 2018

How DAOs take the Agent “Off the Books” - Business Insider