What’s Inflation?

In simple terms, inflation is the general increase in the price of goods and services in the economy. Inflation weakens the purchasing power of one’s money, increasing the cost of living.

As inflation occurs, workers demand higher wages from their employers to compensate for the higher cost of living. Consequently, their employers must increase the cost of the goods and services they are selling to remain profitable while paying these higher wages, which leads to further inflation. This is the Vicious Cycle of Inflation: as inflation occurs, its ripple-effect across the economy tends to further drive even more inflation.

One of the primary goals of the Federal Reserve, the US Central Bank, is to ensure price stability within our economy. Contrary to what many think, price stability, in the eyes of the Federal Reserve, does not mean keeping prices the same with an inflation rate of 0%. Instead, the Federal Reserve seeks to maintain an inflation rate of about 2%, as it signifies the economy growing at a healthy rate.

To fight inflation significantly above this approximately 2% rate, our economic policy makers adopt contractionary policies: the Federal Reserve enacts contractionary monetary policy by raising interest rates and decreasing the money and credit supply, and the President and Congress enact contractionary fiscal policy by decreasing government spending and increasing federal income taxes.

How do we measure inflation?

Economists and consumers vary in the ways that they track inflation and make tangible its effects.

The most common inflationary index is the Consumer Price Index (CPI), a price index which measures inflation for urban consumers by pricing a basket of consumer goods — food, clothing, housing, medical care, entertainment, transportation, energy, and other items. While it is very widely used, many argue that the CPI’s measure of inflation is a poor indicator of long-term inflation because it contains volatile food and energy prices, which fluctuate greatly due to weather, political events, etc. As such, the CPI can be a misleading gauge of long-term inflation because it moves up and down with every temporary fluctuation in food and energy prices.

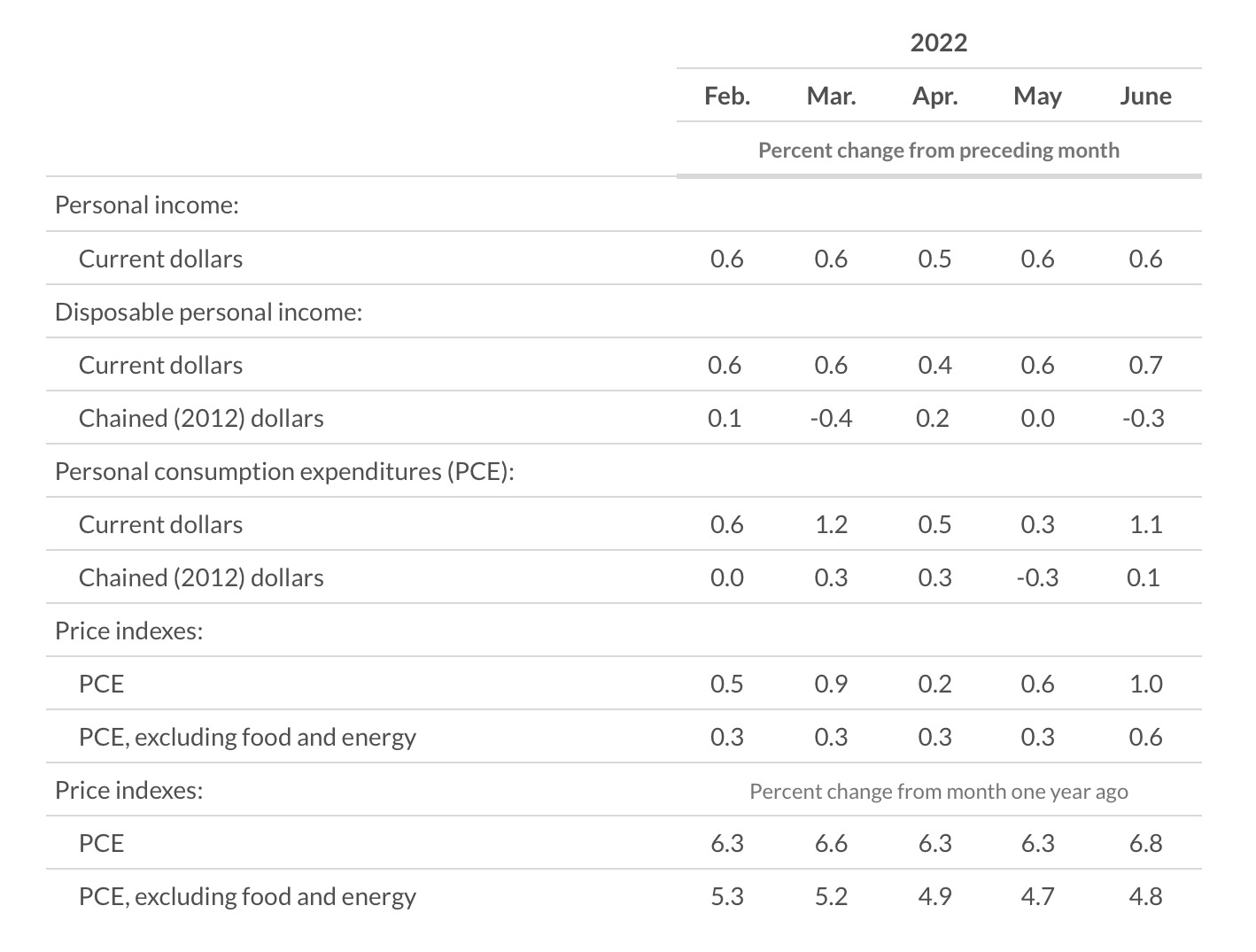

So, to determine a more accurate long-term gauge of inflation, the Federal Reserve removed food and energy prices from the inflationary indices and created a Core Inflation Index called the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) Index. Using core inflation measurements, the Federal Reserve better knows when it is wise to step on the monetary brake and enact contractionary monetary policy to slow inflation, and when it is okay for the economy to be left alone.

How does inflation impact me?

Quite simply, as inflation occurs and the dollar loses its purchasing power, consumers pay more for equivalent goods. For example, this July, the average cost of a 4th of July barbecue for 10 cost $69.68, or about $6.97 a person, 17% more than last year due to inflation.

However, the impact of inflation on households varies largely due to geographic location, consumption habits, etc. For example, energy prices have inflated about 40% over the past 12 months (also impacted by the OPEC+ supply dispute of Summer ‘21), food prices 10%, apparel 5.2%, new vehicles 11.4%, and medical care 4.8%. Thus, depending upon how reliant a family is on various sectors, they might be hurt far more or far less by the recent inflation.

While some households can afford to pay this increased amount, others can not. And those impacted most tend to be the less fortunate in our society.

Our Current Dilemma…

…is quite confusing, to say the very least. Economists chalk up our current inflation to several causes:

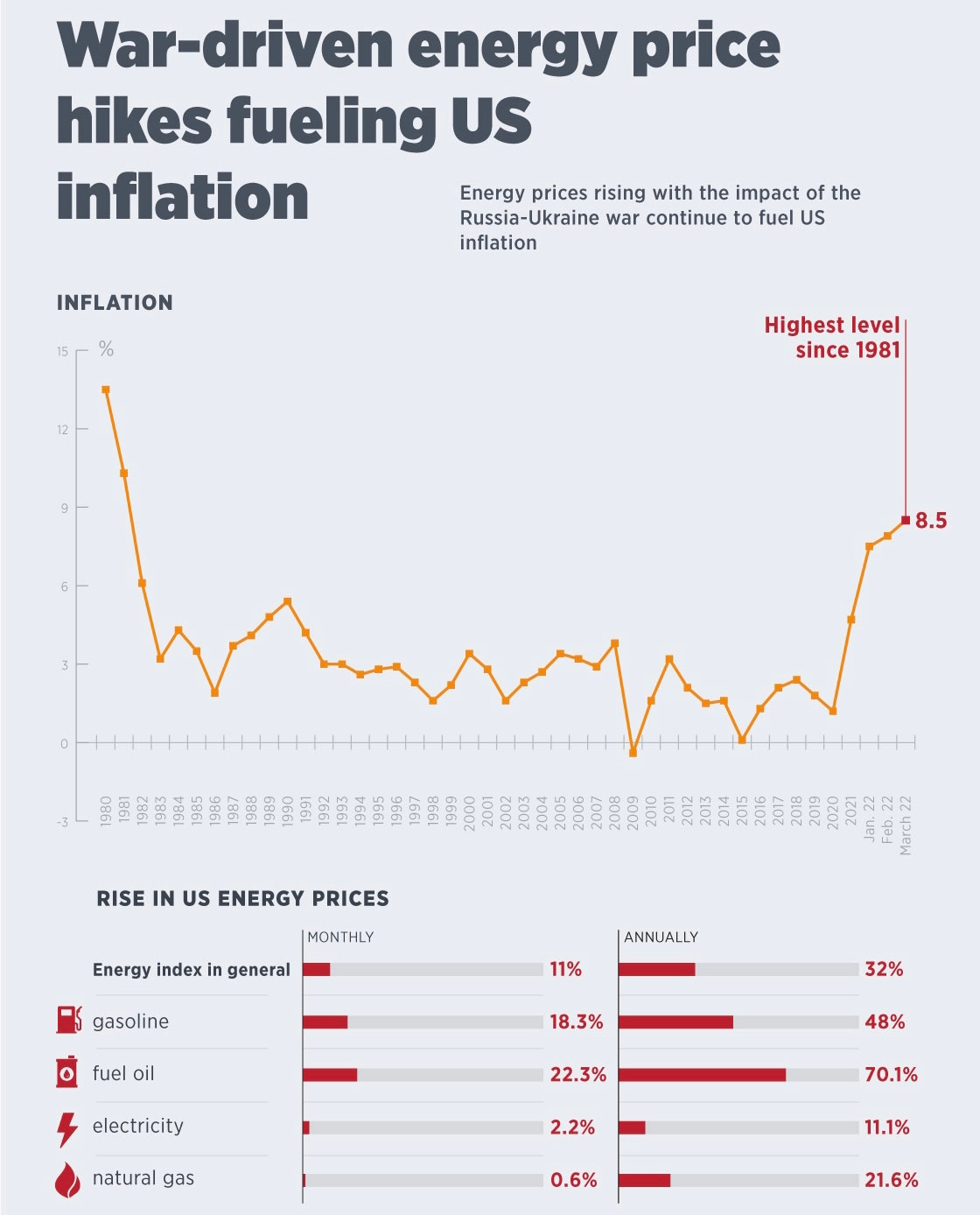

First, and perhaps most important, is the conflict between Russia and Ukraine, especially on the price of oil. As the US and the rest of the West sanctioned Russia, the second-largest exporter of oil in 2021, in an attempt to cripple its economy, the price of oil surged. Further, the war has both increased the demand for food and prevented Ukraine, the fourth-largest agricultural exporter in 2021, from supplying food globally, driving up food prices globally.

Second, the expansionary monetary and fiscal policies adopted by US policymakers during the COVID-19 pandemic continue to have rippling effects. The increase in government spending necessary to enact the Payroll Protection Program and various other forms of pandemic relief, when coupled with the lowering of the Fed Funds rate to a range of 0% to 0.25% and the enacting of quantitative easing—the Fed’s purchasing massive amounts of debt securities—in support of the economy, began to overheat the economy and drive up inflation.

Third, supply chain issues have also contributed to growing inflation. As various global issues have created adverse supply shocks, supply has decreased, driving down the quantity and driving up the price of goods. For example, delayed semiconductor production due to COVID-caused shutdowns, backed-up shipping ports, and a growing industry shift towards electric vehicles has had a widespread impact on supply and prices: The lack of semiconductors has slowed automobile production and led to a surge in car prices, among other related impacts on computers and other technology.

As of June, the current YoY CPI Inflation Rate is 9.1%, and the current YoY PCE Core Inflation Rate is 5.9%, both far higher than the desired 2% rate. As such, on July 27, the Federal Reserve announced it was hiking interest rates by 75 basis points for a second consecutive time, raising the Federal Funds target rate to 2.25%-2.5%.

To make things even more complicated, an advance estimate states that GDP contracted 0.9% in the second quarter of 2022— the second straight quarter in a row—sounding the alarm for a recession. While those at the National Bureau of Economic Research define a recession using several more nuanced criteria such as employment, retail sales, and industrial production, much of the US public takes the second straight quarter of contracting GDP to signal a recession and have criticized the White House’s saying otherwise as an attempt to protect its reputation.

Consequently, many US Economists are beginning to fear a bout of Stagflation: the dangerous combination of inflation and a contracting (stagnating) economy. Stagflation poses an especially challenging policy issue since its two issues are solved by opposite monetary/fiscal policies: Taming inflation requires contractionary monetary/fiscal policy, while boosting output and employment requires expansionary monetary/fiscal policy.

Back in the 1970s, largely due to two adverse oil supply shocks, the US economy experienced Stagflation. And it was the policy idea of then-Fed Chair Paul Volcker which eventually solved the Stagflation of the ‘70s: First, the Federal Reserve enacted contractionary monetary policy to kill off inflation, and then, once inflation was gone, enacted expansionary monetary policy to rebound output and employment.

What’s next?

Frankly, economists aren’t sure. Many questions remain: Are we officially in a recession? Have we entered a bout of Stagflation? If so, will the ‘Volcker Solution’ work again? Is a different policy mix necessary to combat such an economic disease this time around? How will the military conflicts in Ukraine continue to impact the supply of goods and their prices?

We’ll see in the coming months. Pay keen attention to how the Federal Reserve continues to adjust monetary policy and how the President and Congress react to and speak on changing economic themes. Their words, predictions, and actions serve as a great indicator of how the economy will trend and how investments will perform — making them greatly valuable to all.

Further Readings…

How Milton Friedman Changed Economics, Policy and Markets - WSJ

Includes history of inflation and Paul Volcker’s implementation of the Monetarist Theory

Presidential Economics - Book

History of federal government response to inflation